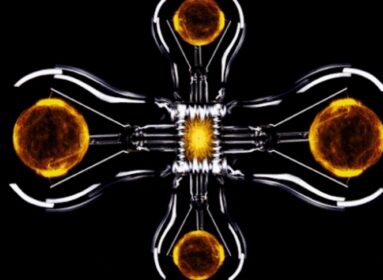

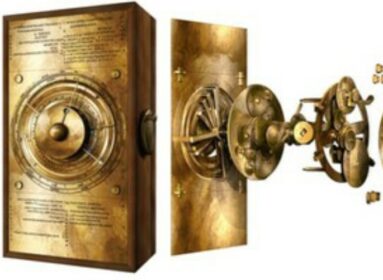

A digital model of how the calculator may have looked and worked in the first century B.C. PHOTO BY UCL

The calculator which is more than 2,000 years old is said to be able to predict the movement of five known planets as well as the phases of the moon and solar and lunar eclipses.

For more than 100 years, scientists have deliberated the mystery behind the ancient Antikythera mechanism, a 2,000-year-old Greek astronomical calculator with the ability to exhibit the movement of the universe, including five known planets and predict the phases of the moon and the solar and lunar eclipses.

Currently only a third of the device — often defined as the world’s first analogue computer — remains in a collection of 82 battered fragments, including 30 corroded bronze gearwheels, further baffling scholars.

Researchers also don’t know why the Antikythera mechanism was built. It could have been a toy, or a teaching tool, they posited.

“Although metal is precious, and so would have been recycled, it is odd that nothing remotely similar has been found or dug up,” Wojcik said. “If they had the tech to make the Antikythera mechanism, why did they not extend this tech to devising other machines, such as clocks?”

However, researchers at the University College of London believe they may have finally cracked the code and hope to prove it by building a replica using modern machinery to test their theory. “We believe that our reconstruction fits all the evidence that scientists have gleaned from the extant remains to date,” Adam Wojcik, a materials scientist at UCL, informed.

If their theory is correct, then they hope to rebuild the mechanism using a technique from antiquity, they wrote in a paper published by science journal Nature.

The calculator first came to light in 1901 after it was recovered by sponge divers looking for treasures within an archaic ship sunken off the coast of Antikythera, a Greek island. Scholars believe the ship sank during a storm in the first century BC while passing between Crete and the Peloponnese while en route to Rome from Asia Minor.

The device is heavily corroded, but scholars examining it noticed several inscriptions on the mechanism, which provide a kind of user’s manual to operating the calculator. It also included more than 30 bronze gearwheels connected to dials and pointers.

The team believe that the device may have displayed the movement of the sun, moon and the planets Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn on concentric rings. However, as the calculator assumes that the sun and planets revolve around the Earth, the planets’ paths are much more difficult to recreate than if the Sun was at the centre.

They also propose adding a hypothetical feature, called the ‘Dragon Hand’ that indicates when eclipses would happen, to replace a similar hand once used by the clock. “The way that the Saros Dial on the Back Plate predicts eclipses essentially involves the lunar nodes , but they are not described in the extant inscriptions,” the paper reads. Lunar nodes are where the Moon’s orbit intersects that of the Earth.

The UCL team wrote that it drew on the works of previous scholars and engineers to reconstruct the mechanism, particularly that of Michael Wright.

Wright, a former mechanical engineer at the Science Museum of London, was instrumental in figuring out how most of the mechanism work, enough to build a working replica. Drawing on his work, researchers used inscriptions on the mechanism and a mathematical method described by Parmenides, an ancient Greek philosopher, to design gear arrangements to move planets and other bodies correctly.

Their solution allows nearly all of the mechanism’s gearwheels to fit within a space only 25 mm deep.

Though hopeful, it isn’t clear whether the new model could accurately replicate the workings of the calculator. For one, the concentric rings that constitute the calculator’s display would have to rotate on a set of nested, hollow axles, and researchers aren’t sure how ancient Greeks would have made the mechanism possible without a modern-day lathe (a machining tool used to shape or rotate metal and wood).

“The concentric tubes at the core of the planetarium are where my faith in Greek tech falters, and where the model might also falter,” said Wojcik. “Lathes would be the way today, but we can’t assume they had those for metal.”

Source: National Post

Comments are closed.