The Gateway of the Sun, Tiwanaku, Bolivia. Image credit: Mhwater.

Archaeological records play a role in connecting cultures, studying ancient DNA can provide a finer grain picture.

A large international team of researchers has conducted the first in-depth, wide-scale study of the genomic history of pre-Columbian Andean civilizations such as the Moche, Wari, Tiwanaku, Nazca, and Inca. Published in the journal Cell, the findings reveal early genetic distinctions between groups in nearby regions, population mixing within and beyond the Andes, surprising genetic continuity amid cultural upheaval, and ancestral cosmopolitanism.

“There are many unanswered questions about the population history of the central Andes and in particular the large-scale societies that lived there,” said co-author Dr. Bastien Llamas, a researcher in the Australian Centre for Ancient DNA at the University of Adelaide.

“We know from archeological research that the central Andes region is extremely rich in cultural heritage, however up until now the genomic makeup of the region before arrival of Europeans has never been studied.” “While archaeological records play a role in connecting cultures, studying ancient DNA can provide a finer grain picture.”

“For example, archaeological information may tell us about two or three cultures in the region, and eventually who was there first, but ancient DNA can inform about actual biological connections underlying expansion of cultural practices, languages or technologies.”

In the study, Dr. Llamas and colleagues sequenced and analyzed the genomes of 89 individuals who lived between 500 and 9,000 years ago and compared the data with the genetic diversity of present-day occupants.

Of these, 64 genomes, ranging from 500 to 4,500 years old, were newly sequenced — more than doubling the number of ancient individuals with genome-wide data from South America.

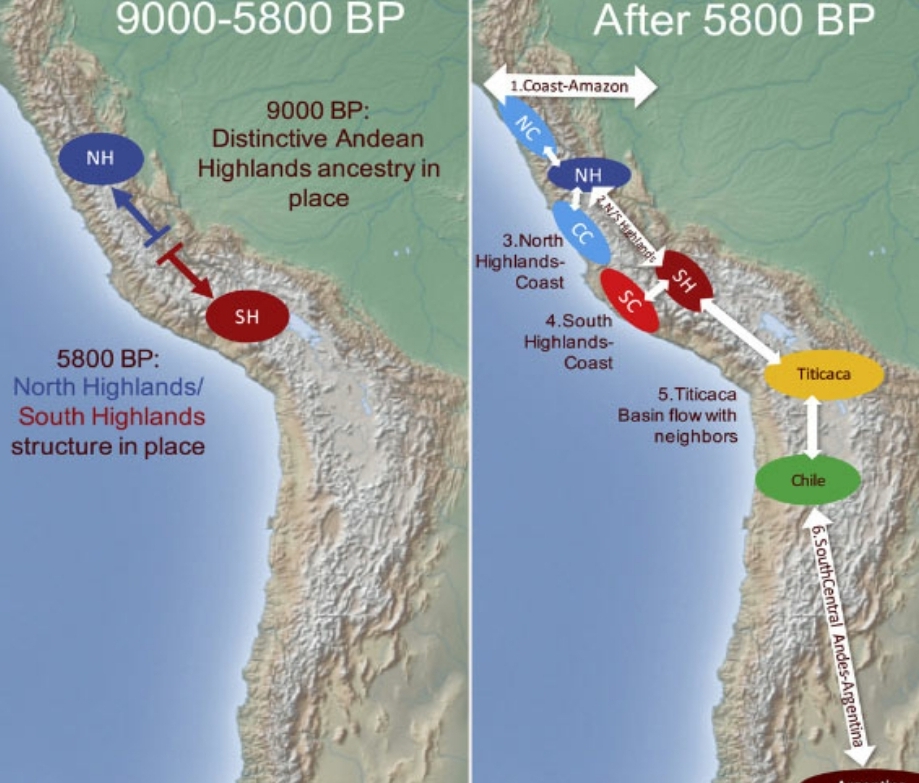

The scientists found that by 9,000 years ago, groups living in the Andean highlands became genetically distinct from those that eventually came to live along the Pacific coast. The effects of this early differentiation are still seen today.

“The genetic fingerprints distinguishing people living in the highlands from those in nearby regions are remarkably ancient,” said first author Nathan Nakatsuka, an MD/PhD student in the Department of Genetics at Harvard Medical School and the Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology.

“It is extraordinary, given the small geographic distance,” added senior author Professor David Reich, a researcher in the Department of Genetics and Howard Hughes Medical Institute at Harvard Medical School, the Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT, and the Department of Human Evolutionary Biology at Harvard University.

By 5,800 years ago, the population of the north also developed distinct genetic signatures from populations that became prevalent in the south. Again, these differences can be observed today.

After that time, gene flow occurred among all regions in the Andes, although it dramatically slowed after 2,000 years ago.

“This was quite surprising given this period saw the rise and fall of many large-scale Andean cultures such as Moche, Wari and Nazca, and suggests that these empires implemented a cultural domination without moving armies,” Dr. Llamas said.

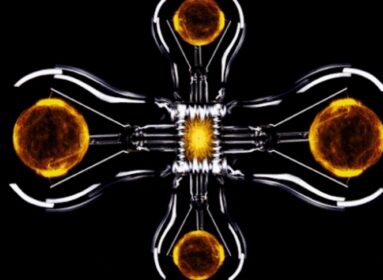

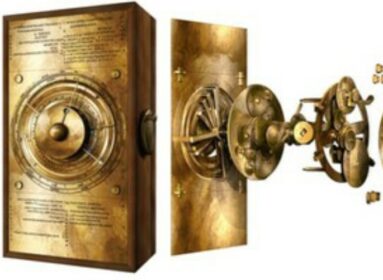

Nakatsuka et al assembled genome-wide data on 89 individuals dating from 9,000-500 years ago, with a particular focus on the period of the rise and fall of Andean state societies. Today’s genetic structure began to develop by 5,800 years ago, followed by bi-directional gene flow between the North and South Highlands, and between the Highlands and Coast; the researchers detected minimal admixture among neighboring groups between 2,000-500 years ago, although they didn’t detect cosmopolitanism (people of diverse ancestries living side-by-side) in the heartlands of the Tiwanaku and Inca polities. Image credit: Nakatsuka et al, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.015.

There were two exceptions to the slowing of migration, and these were within the Tiwanaku and Inca populations, whose administrative centers were largely cosmopolitan — people of diverse ancestries living side-by-side.

“It was interesting to uncover signs of long-range mobility during the Inca period,” Dr. Llamas said.

“Archaeology shows the Inca occupied thousands of miles from Ecuador through to northern Chile — which is why when Europeans arrived they discovered a massive Inka empire, but we found close genetic relationships between individuals at the extreme edges of the empire.”

“It is exciting that we were actually able to determine relatively fine-grained population structure in the Andes, allowing us to differentiate between coastal, northern, southern and highland groups as well as individuals living in the Titicaca Basin,” said senior author Dr. Lars Fehren-Schmitz, a scientist in the Genomics Institute at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

“This is significant for the archaeology of the Andes and will now allow us to ask more specific questions with regards to local demographics and cultural networks,” said co-author Dr. Jose Capriles, a researcher in the Department of Anthropology at the Pennsylvania State University.

Source: Sci-news l Cell.

Comments are closed.